Ben Stanley

July 17, 2024

When it comes to America’s fast-growing lithium brine industry, there are few places more important than Union County, Arkansas.

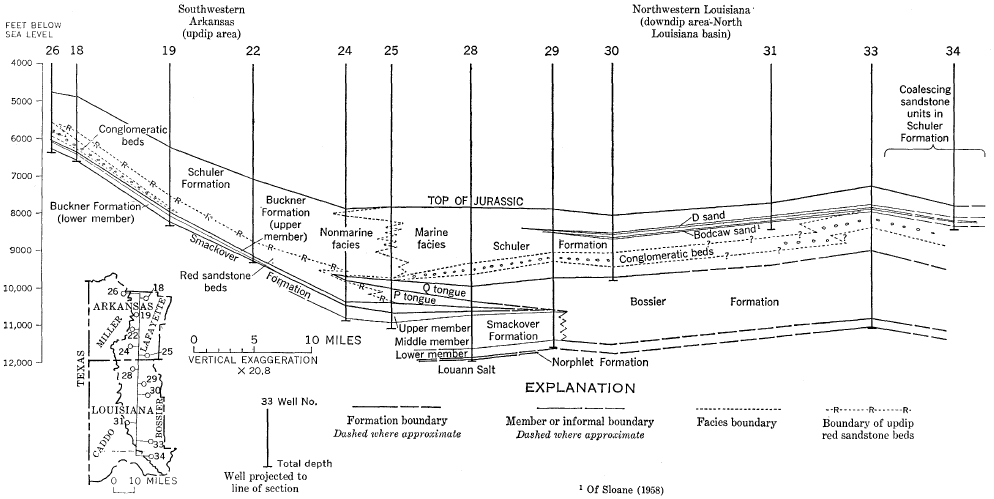

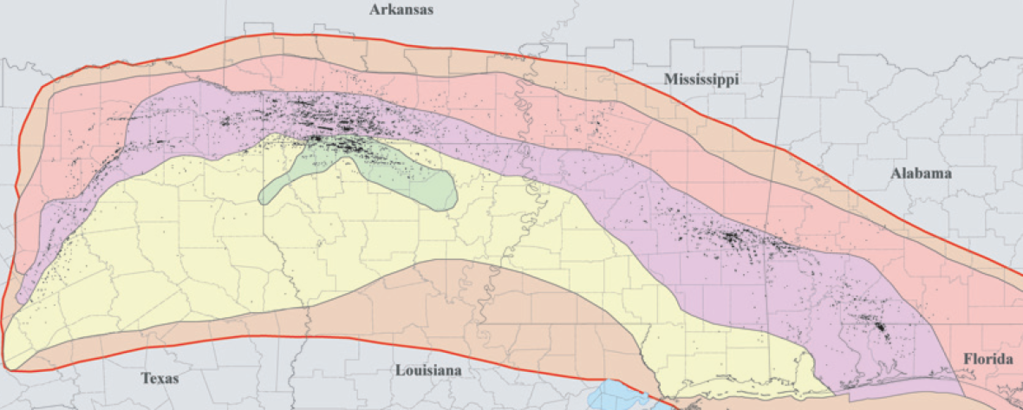

Located on the Louisiana border, Arkansas’s largest county sits above the Smackover Formation, a three-state geological area that has provided the United States with oil and bromine since the 1920s.

Though relatively high lithium concentrations have long been detected in South Arkansas oilfield brine, a range of factors—from different impurity profiles and climate to limited space and public support for large evaporation ponds—have meant extracting it hasn’t been possible. Now it looks likely that Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) technology will soon change the game.

Oil industry heavyweight ExxonMobil, lithium giant Albemarle, and a partnership between Standard Lithium and Equinor are committed to lithium production in the region. All three have Union County-located leases, with Standard Lithium’s DLE pilot column currently in advanced testing.

While a DLE-powered lithium boom will be welcomed in the county seat of El Dorado and the state capital of Little Rock, recent decades have seen Union County’s place in the American resource landscape best defined by how well it has managed and conserved its groundwater.

Faced with a fast-diminishing water table in the late 1990s, Union County residents instituted a nation-leading groundwater management scheme that has almost completely recharged the Sparta Aquifer—located above the lithium-rich Smackover—while enabling bromine brine extraction to continue. The South Arkansas plan came decades before the public alarm and widespread state legislature reaction to America’s current groundwater depletion crisis.

Given that one of the key questions around DLE’s commercial feasibility is how much fresh water the technology will use, it almost seems fated that this early American road test of selecting separating lithium ions from lithium-rich brine would take place in South Arkansas.

“If we cannot do a good job of recycling that water and reducing our water footprint, we’re going to get crushed,” John Burba, executive chairman of International Battery Metals, told Reuters last September, talking about DLE’s fresh water usage. “DLE is a very water-intensive process.”

Responding to a Diminishing Resource

Groundwater is the world’s most extracted raw material, providing almost half of global drinking water. Around 70 percent of all groundwater extracted is used by agriculture, which plays a significant role in ensuring we stay fed.

States with large populations and extensive farmlands tend to have the most significant groundwater withdrawals in America. In 2015, just five states—California, Texas, Idaho, Nebraska, and Arkansas—accounted for 54 percent of national groundwater use, primarily for irrigation.

Across the board, excessive water pumping, increasing droughts, and government incentives to increase food production have all affected aquifer recovery time. The overall result has been troubling.

Last August, the New York Times published an extensive investigation on groundwater usage in the United States. The findings were damning. After analyzing water levels at more than 80,000 monitoring wells across the U.S., the Times found that nearly half have “declined significantly [since the early 1980s] as more water has been pumped out than nature can replenish.”

Since 2014, 40 percent of sites have hit all-time lows. Top agricultural producers, like the ones listed above, are amongst the worst-performing states.

“From an objective standpoint, this is a crisis,” Warigia Bowman, a law professor and water expert at the University of Tulsa, told the Times, “There will be parts of the U.S. that run out of drinking water.”

Nearly three decades ago, Union County saw this coming — and acted. In 1996, the Arkansas state government designated the Sparta Aquifer beneath South Arkansas as a ‘Critical Groundwater Area.’

The following year, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) found the aquifer was dropping by as much as two meters a year. It recommended that future groundwater withdrawals in Union County be cut by nearly three-quarters to maintain water levels. Industrial requirements for freshwater played a big role in the aquifer’s diminishment.

“If we didn’t do something in five years or less, we were going to lose our water source,” Sherrel Johnson, the projects manager for the Union County water conservation board, told the Scientific American earlier this year.

Union County residents petitioned Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee—father of current Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders—to appoint a Water Conservation Board endowed with the authority to tax.

After kicking off a county-wide education program about the state of their aquifer, the board enacted a ‘conservation’ pumping fee for industrial users. Next, it instituted a voter-endorsed temporary tax for a $65 million treatment plant, drawing surface water from the nearby Ouachita River. The treated river water was explicitly for industrial users, placing far less pressure on the previously vulnerable water table.

The result of the water board’s moves has been a smashing success. This year, the overall level of the Sparta Aquifer was 36 meters higher than in 2004. All eight of USGS’s monitoring wells across the county have shown continual increases over the last two decades. In April, one well showed water levels were now higher than the top of the aquifer itself.

“You have to have trusted leadership, [good] science, and tenacity [to make the necessary changes],” Johnson said.

Union County isn’t alone in its efforts around the U.S. Aquifer Storage and Recovery schemes are active in cities across the Western United States, with Austin, San Antonio, and California’s Central Valley leading the way.

Since 2008, the $450 million San Juan-Chama Project has led to the recovery of the aquifer beneath Albuquerque, New Mexico, and lifted fresh water supplies for farmers along the Rio Grande River.

Positive Steps Forward

At best, the Federal approach to America’s groundwater crisis could be called stunted. At worst? Deeply disappointing. Over recent years, Senator Martin Henrich, a New Mexico Democrat, has championed the cause of groundwater management and conservation in Washington, D.C., introducing a raft of bills.

His Voluntary Groundwater Conservation Act—co-sponsored by Senator Jerry Moran, a Republican from Kansas—would give American farmers more flexibility and incentives to protect groundwater sources. Heinirch's Water Data Act has the potential to transform water management by establishing a national requirement for collecting information about groundwater.

Currently, many states require little, if any, monitoring or reporting on their aquifers. For their deeply researched investigation into the state of American groundwater, the Times used figures from 60 different databases, each with its categories of interest and levels of completeness.

Neither of Heinrich’s bills have been voted on.

Further down the American governance chain, there’s more encouraging movement. Last October, the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), a bipartisan group representing state governments across the U.S., highlighted many encouraging groundwater-focused laws passed in red and blue states over recent years.

Since 2019, more than 100 state bills focusing on groundwater conservation and management have been made law. In the last two years, Virginia, Idaho, Kansas, Utah, and Nevada all passed laws that focused on conserving aquifers and basins.

Passed in 2020, the Utah Water Banking Act has enabled water rights holders with extra water to lease it to those with less. The state is planning on expanding the program. Along with revising current groundwater management provisions, Nevada introduced a law last year that requires the state engineer to “affirm or modify the perennial yield of basins in designated critical management areas.” Both Utah and Nevada have a crucial role in America’s lithium future.

Extraction policies have changed, too. A number of states require further permitting, higher fees for extraction in conservation areas, and plans for water auditing and leak detection and repair. California, Oklahoma, Nevada, Texas, and Virginia are among the states leading the way.

Other measures are possible. Writing for Forbes last October, John Sabo, a Tulane professor focusing on water resources at the school’s ByWater Institute, identified three ways to improve the groundwater situation in the Mississippi River Valley.

These were determining how to better capture excess water from downpours and floods and store it underground, establishing an interstate compact to help coordinate conjunctive groundwater and surface water management, and reevaluating how water is used in agriculture, including which crops are grown where.

There are international examples to replicate, too. Several recharge pilot schemes in central Spain have utilized rooftop runoff and treated wastewater to refill aquifers. After new fees were introduced for private well pumping in Bangkok in the early 2000s, groundwater losses were reversed, and land subsidence issues slowed.

Back to Union County

Since 84 percent of all groundwater withdrawals are freshwater, the extraction of saline aquifers makes up less than a sixth of all water drawn from beneath the surface in the United States.

Ninety-seven percent of saline groundwater is used for thermoelectric energy, two percent for industrial needs, and just one percent for mining—a figure that will quickly increase as drilling for DLE-enabled brines becomes more feasible and environmentally friendly.

The entire lithium industry has been working on strategies to increase freshwater recycling, aiming to ensure lithium extraction from brine remains feasible from a resource management standpoint. Freshwater requirements for DLE will vary from design to design.

Reuters reported that some types of DLE technology require 180 metric tons of water to produce one metric ton of lithium, which does little to support DLE’s transformational claims. In the ion-exchange DLE process, for instance, fresh water is required to rinse the sorbent from the lithium. Careful recycling of this freshwater input will in many instances also be required.

Last year, French researchers published a paper on the environmental impact of DLE from brines. After analyzing 57 reports on water-dependent DLE technology, they found a quarter showed freshwater usage at rates up to ten times higher than evaporation ponds used in South America. Another quarter of the DLE tech they studied had no freshwater usage data at all.

Encouragingly, Albemarle uses membrane-based DLE tech at its Union County pilot plant, a technique that some recognize as requiring less water for operations. ExxonMobil is still researching which DLE technology to use, while Standard Lithium has spoken with confidence about the efficency of their Koch Industries-engineered system.

Due to the presence of the Ouachita River and the county’s treatment plant, fresh water is relatively abundant on the Arkansas side of the Smackover. Industry has continued successfully in Union County, utilizing water from the plant. Since 2007, all of America’s bromine supply has been sourced from South Arkansas brine.

Johnson, of the Union County Water Conservation Board, says their publicly funded water plant has “proven a boon for luring new development,” which includes lithium brinefield operators.

Another challenge lithium miners face in Union County is that the Sparta Aquifer sits directly above the Smackover itself. Careful engineering and properly designed drilling and pumping technology is an absolute must.

Whatever happens, you can be sure the Union County Water Conservation Board will be watching the levels. In one of DLE tech's early road tests n South Arkansas brine, a suitable water watchdog is firmly in place.

Recent Posts

Using Digital Twin Technology in the Lithium Brine Industry

How the Inflation Reduction Act and US Trade Policy Could Handicap Its Ability to Harness Argentine Lithium Supply

The Lithium Brine Industry Must Share Reinjection Best Practices

Key Argentine Mining Leader, Flavia Royon, Joins Zelandez Board

Lithium Partnership with Argentinian Province Set to Benefit US Lithium Supply