When we look back in a decade's time, how will we think of the lithium market of today?

I think we’ll remember 2024 as the year that Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) got its first real road test.

Several DLE projects are now being commissioned— for example Centenario-Ratones, Argentina (Eramet)—with many feasible opportunities to work at scale. DLE plants in South Arkansas and California yield promise, with many more concepts getting closer to the commercial phase.

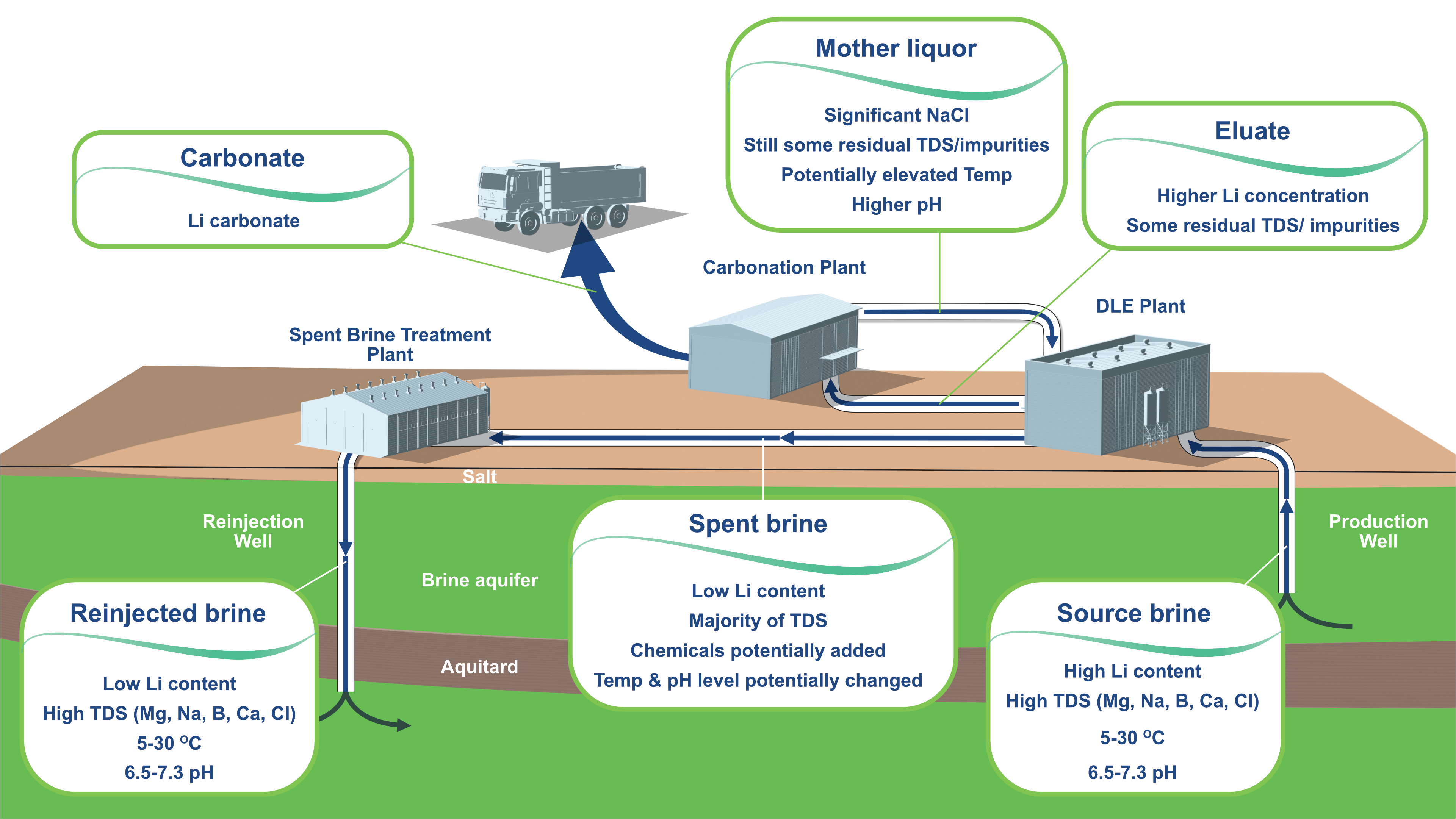

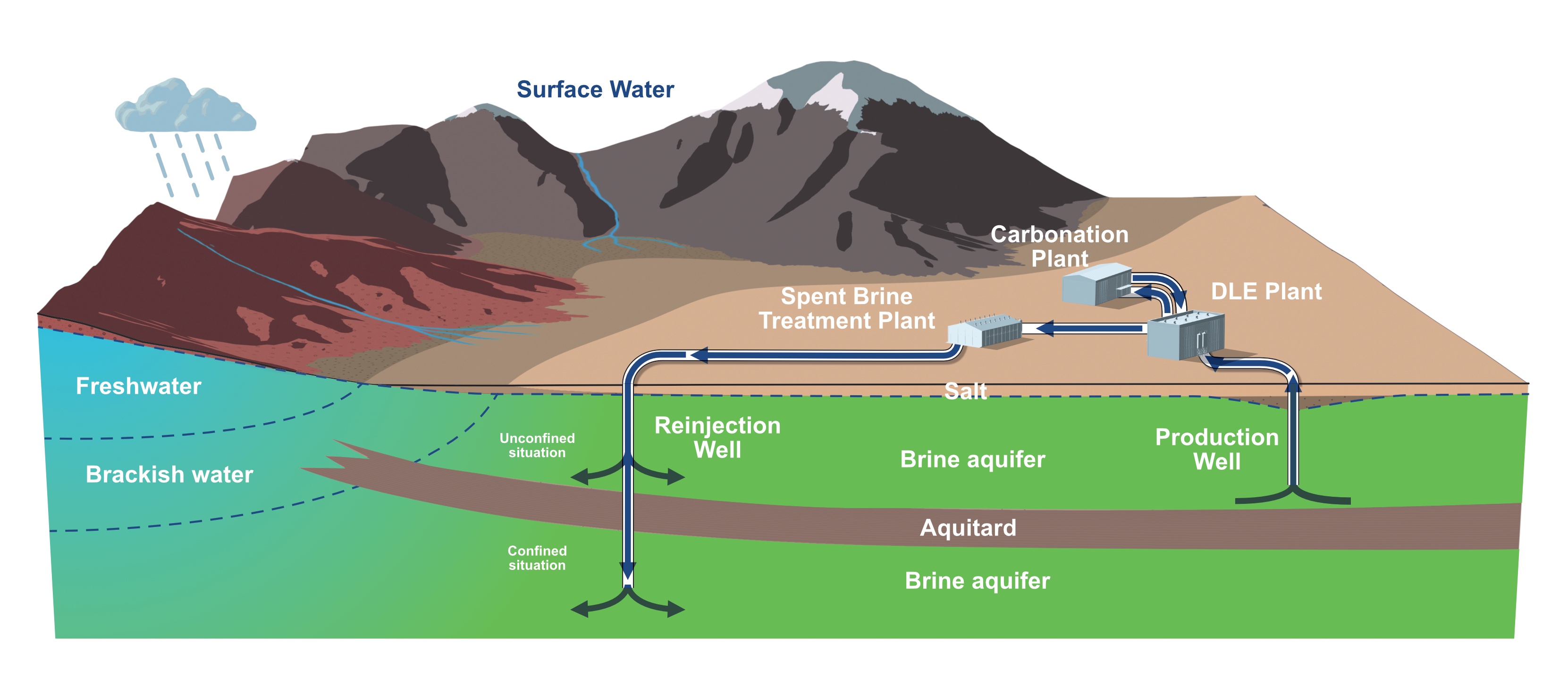

The shift from evaporation ponds to DLE in South America will immediately create a new problem.

It is a solvable problem—with deep wells of knowledge that are transferable from the Oil & Gas industry—but it is a substantial problem nevertheless:

Where does all the liquid go once you’ve extracted the lithium?

The issue of reinjection—or, as we see it, “brine recycling”—is now arguably the number one issue in the lithium brine sectors of Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia.

For many projects it is now the critical path.

At the moment each project is engaging in its brine recycling efforts individually, acting in relative silos. And for the most part the regulators and lawmakers are at sea, without a strong knowledge-base of the best practices. From the provincial to national levels, there is little in the way of frameworks or standards for miners to follow, in order to reinject their spent brine responsibly.

The stakes are high, and we think that the lithium industry should come together and discuss what best practices should be deployed. That’s something that Zelandez is willing to invest in.

This week Zelandez published a white paper, with input from more than a dozen respected industry players, addressing best practices for recycling and reinjecting spent lithium brine. The 80-page document, ‘Recycling Brine for a Greener Future,’ contains what is understood to be the first guidelines for spent lithium brine best practices. Albemarle, SQM, Eramet, Arcadium, and Hatch are among those who have reviewed and had input on the paper.

Although Zelandez has offered a specialized spent brine reinjection service since 2023, this new work collaborating with the industry, has resulted in what we hope is a foundational document. It is something we could not have completed on our own.

Let's state the obvious. Poor reinjection technique could damage brine formations and potentially lead to significant financial and environmental repercussions. That's not something we can accept. At the end of the day, good brine recycling must align with the principles of responsible, sustainable resource management.

The incredibly encouraging thing we found as we developed the white paper (alongside the industry) was the learning mindset of the engineers and geoscientists themselves. They are determined to get it right.

Due to the unique makeup of different lithium brine basins, the design of each reinjection process will differ from project to project. So just like DLE, it won’t be a one-size-fits-all approach. But unlike DLE, when it comes to reinjection, we should not keep best practices secret.

Improving the design of well completions, for example, is just one important change that must come in South America. These are the kinds of things we should be thinking about, talking about, and making happen.

To that end, a "brine recycling working group" will be set up—an industry roundtable of sorts. To bring together reinjection practitioners (those people doing the design and engineering). Because as best practice develops, we should aim to share knowledge so that mistakes can be avoided and we can all execute our projects efficiently.

The good news is that the professionals in the lithium brine industry are already taking up the challenge.

The white paper can be found here.

The thanks of Zelandez goes to numerous individual contributors, and to the International Lithium Association and Fastmarkets, along with Summit Nanotech, Albemarle, Arcadium, SQM, Eramet, Hatch, CTR, Power Minerals, Wood, WSP, and Upflow.

Clint Van Marrewijik

August 20, 2024

Column

The use of a Digital Twin is a formidable sounding idea. But is it really relevant, and should the lithium brine market really care?

What is it? The truth is that the term "Digital Twin" is somewhat of an umbrella term, that focuses on delivering results to one of the below key areas:

Practically speaking, that's what they are all about. And these objectives are already being pursued by most lithium brine miners today.

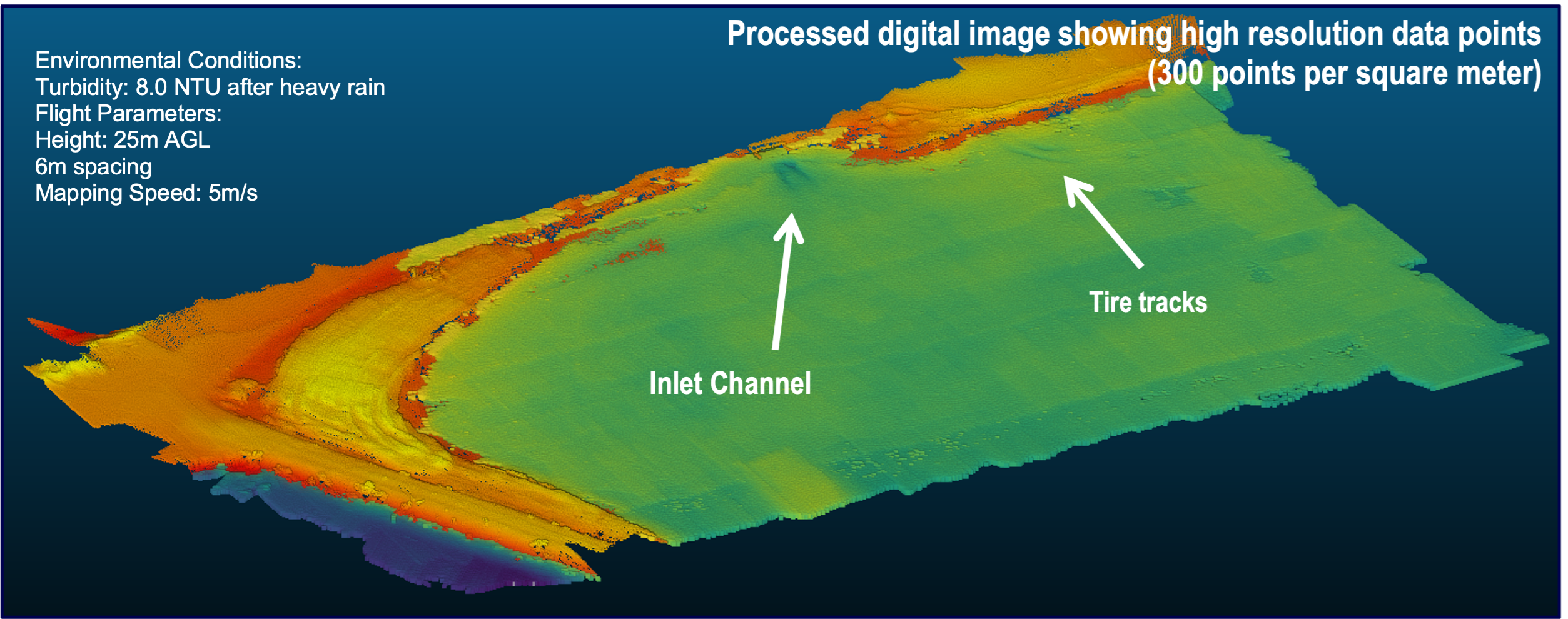

For example, the use of the Zelandez BatSense product. A LiDAR powered drone that feeds data into digital representations of lithium brine ponds, to more accurately represent brine inventory. This more accurate data can significantly impact production performance, and also the efficiency of reagent use.

And with regard to predictive maintenance too. The early use of Digital Twins is happening already, from the brine well-field, right into the aboveground plant.

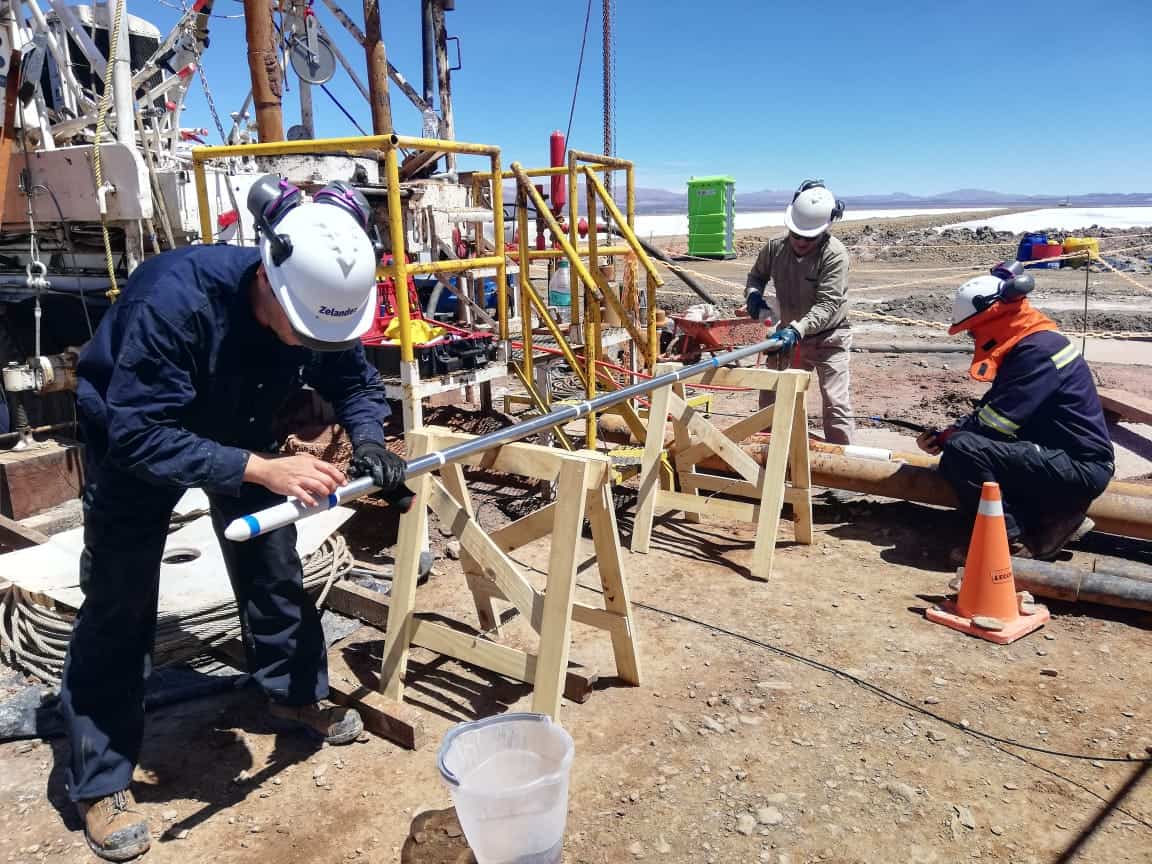

For example most brine producers use the Zelandez Diagnostics and Recovery service on their lithium brine wells.

The corrosion that can happen to lithium wells over time

By knowing in advance the predicted life of each well, upcoming replacement campaigns can be planned before the loss of production starts to impact project cashflow.

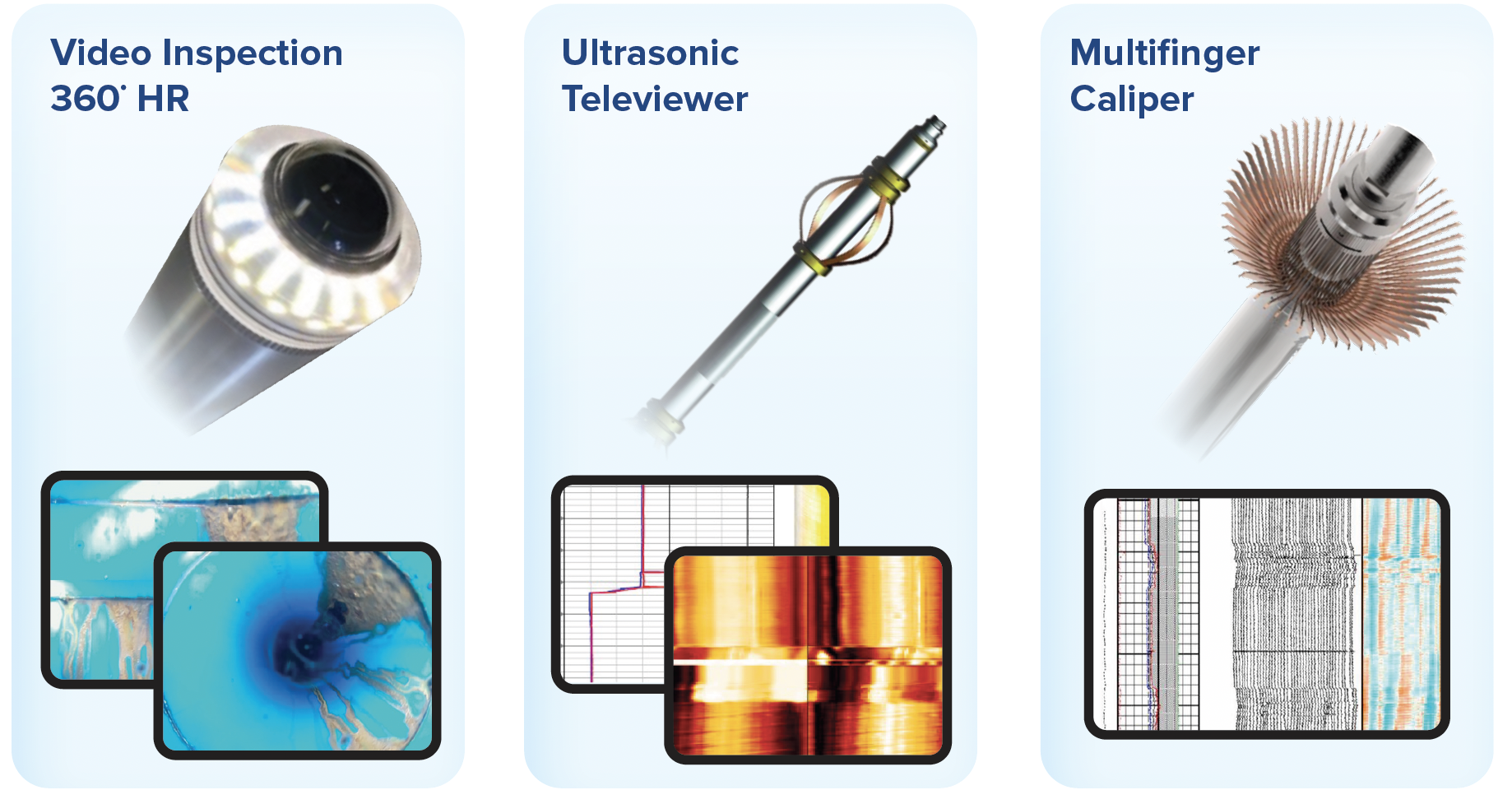

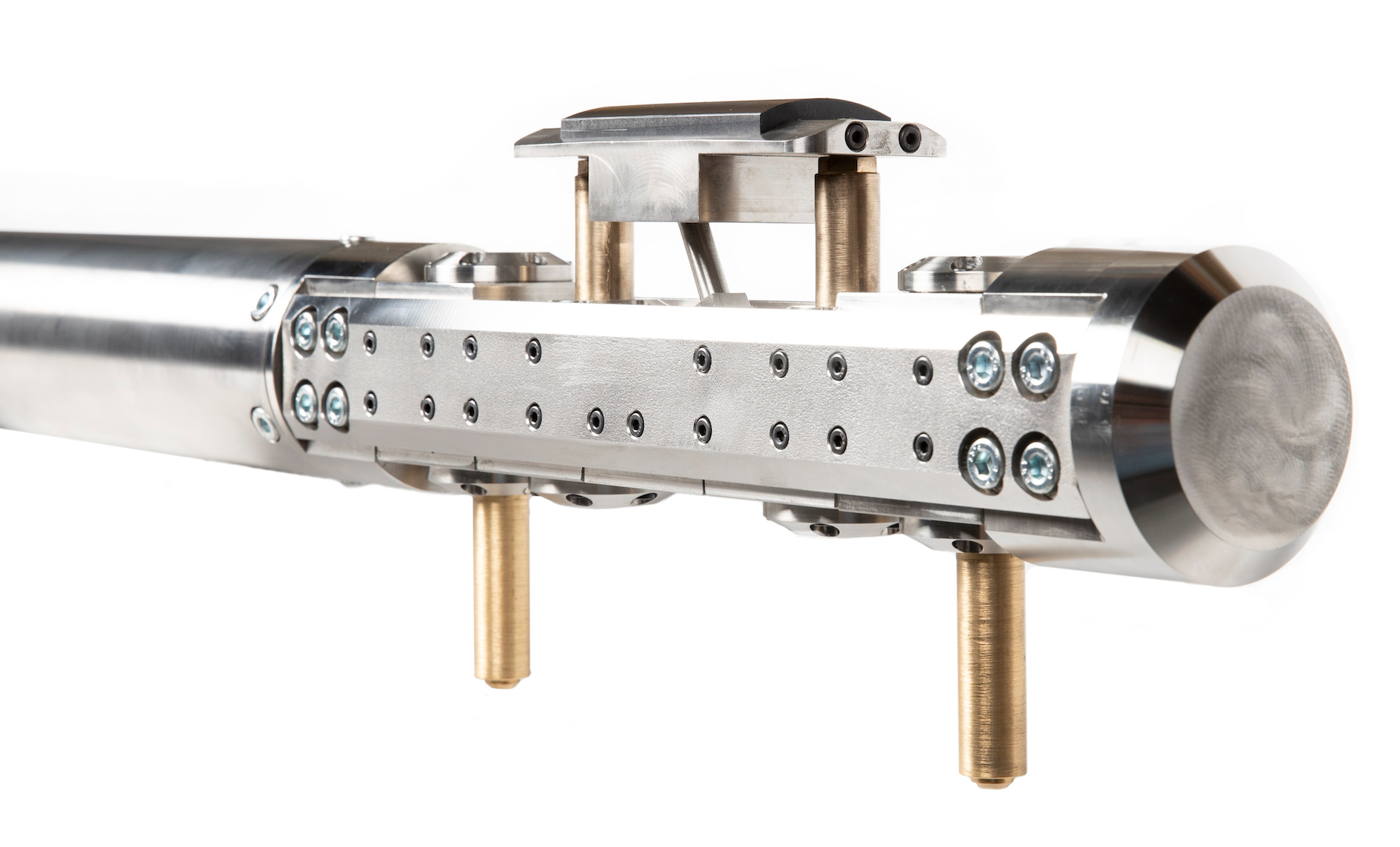

This data itself is gathered by downhole tools that are optimised for lithium brine, feeding into models, so that downtime can be predicted and the stability of the well-field understood.

Tools used by Zelandez in its well Diagnostics service

So in summary then, the term Digital Twin sounds futuristic and new, but it is already happening.

The future is already here.

For more information on Zelandez products, book a meeting with the Zelandez team.

Andrea Bonetto

February 24, 2025

Column

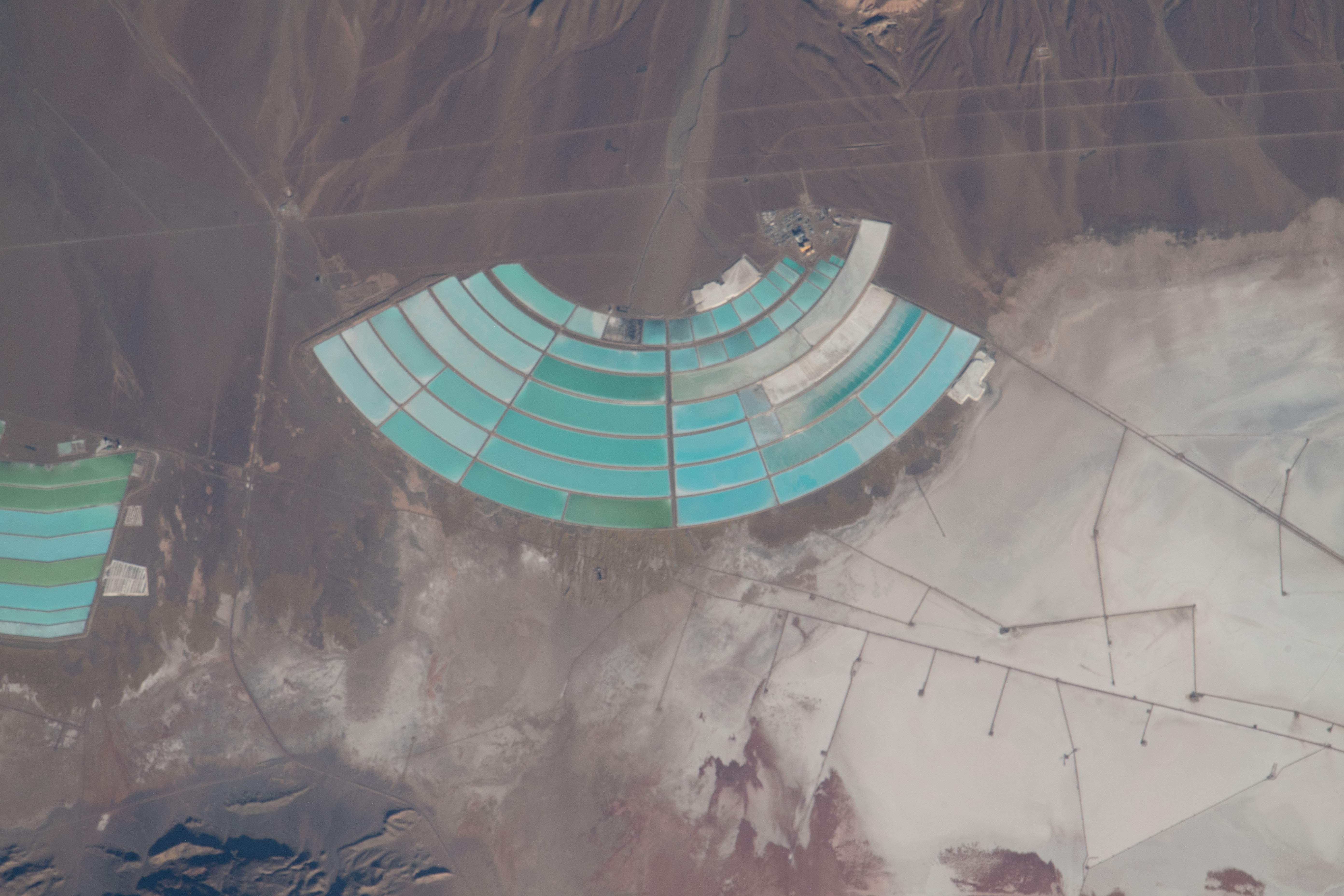

Over the last few months, one of the biggest stories on Argentina’s brine fields has been the opening of Eramet’s Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) plant in Salar Centenario.

The project—built through a major partnership with Chinese nickel and steel heavyweights Tsingshan—is the first time a complete DLE approach has been used to produce lithium in Argentina. It is also the first lithium facility to enter production in Salta province.

French miners Eramet plan to have the plant fully open by November and hope to produce around 25,000 tons of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) by mid-2025. For Argentina, the plant also comes at a time when its burgeoning lithium industry is shifting from second gear to third - and noticeably so.

Argentina produced nearly 50,000 metric tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) in 2023, up from around 37,000 in 2022. Bullish analysts predict it will surpass Chile as the world’s second-largest lithium producer by 2027, while the more conservative ones suggest the early 2030s. Either trajectory would have Argentina’s lithium exports worth billions by the decade’s end.

The lithium landscape is moving, but the United States could miss out on the opportunity that Argentina presents. The lack of a US free trade agreement with Argentina under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) could severely handicap access to the coming wave of high-quality lithium supply from Argentina. Currently, China receives four times more Argentine lithium than the US.

A new mutually incentivised, secure lithium relationship between the US and Argentina is surely essential. To a genuine extent, America’s position as a serious player in the global battery materials supply chain depends on it.

“We are at an important crossroads in the United States’ relationship with Argentine lithium,” Gene Morgan, Zelandez’s chief executive, says.

“The rest of the decade will see Argentina rise as a major player in the lithium industry, but some important loose ends need to be addressed before the US can take advantage of it.”

In 1997, Livent opened the first lithium mining project in Argentina’s history in Salar del Hombre Muerto. Using a hybrid system incorporating both evaporation ponds and early DLE, the plant is still producing today for Arcadium (formed through a merger of Livent and Allkem).

With the opening of Eramet’s plant, four projects are now producing lithium in Argentina. Arcadium also runs the Sales de Jujuy plant in the Olaroz salt flat, while a Ganfeng and Lithium Argentina partnership operates one at Cauchari-Olaroz. Both the Olaroz and Cauchari-Olaroz operations are entirely conventional evaporation pond projects.

Ganfeng, fellow Chinese miners Zijin, and South Korea’s Posco are expected to open new plants in Argentina by the end of 2024, while mining heavyweights Rio Tinto are on track to open a 3,000 ton DLE pilot plant in Salta province.

Six more lithium projects are in the feasibility or pre-feasibility phases, while dozens of junior miners are engaged in advanced exploration. In the context of the current global lithium picture, the level of activity is strong in Argentina.

“[As] higher-cost mines, such as Chinese lepidolite mines, come offline due to not being profitable or sustainable in the current environment, Argentine brines will be well-positioned to take their place,” Aaron Revelle—the chief executive of Pursuit Minerals, who have five leases in Argentina’s Rio Grande salar—told Mining.com.au.

“Oversupply in the market is always a risk to strong growth, but, in the current price environment, Argentine brines are well-positioned for long-term sustainable growth.”

When talking about Argentine lithium, it is important to contrast its state approach to that of neighbors Chile and Bolivia. The three ‘Lithium Triangle’ nations have vastly different state relationships with lithium.

For the last three decades, Argentinian mining has been governed by the 1993 Mining Investment Act. Amongst other incentives, the bill offered stable customs duties, tax incentives throughout the mining process, and no tax on capital goods required for mining. It worked hand-in-hand with the Foreign Investment Act, which saw international investors treated the same as domestic ones regarding mining.

Argentina’s low royalties cap also helped. The 1993 Mining Investment Act stipulates that three percent of all mining profits are returned to the state, a figure a working group of lithium province governors hopes to raise to five. Compared to a progressive royalty system enforced by Chile that can reach 40 percent, Argentina is a more lucrative draw for outside investment. Before 1997, Argentinian mining was pursued only by those seeking copper, silver, and gold.

After constitutional reform in 1994, all Argentina provinces owned their territory’s natural resources and received mining royalties directly. In Argentina, provincial mining agencies hold a great deal of power, overseeing who receives projects and which environmental standards must be adhered to.

“From the national government to the provinces, it is clear that those in power in Argentina are very serious about the health of the lithium sector,” Morgan says. “The level of pragmatism and long-term thinking we’ve encountered is very encouraging.”

Described as Milei’s first major legislative triumph since being elected last December, the recently passed Régimen de Incentivo para Grandes Inversiones (RIGI) builds on Argentina’s existing miner-friendly tax framework.

Benchmark reports that the new legislation offers new miners a ten percent income tax break, a 30-year exemption from new taxes, a reduced dividend tax, a waiver of import duties on capital assets, and a three-year exemption from export duties.

For their first two years, projects can settle 80 percent of their dollar income through the official exchange market. After four years, it drops to zero. The Mining Investment Act’s existing three percent royalty will stay fixed. Australia’s BHP and Canada’s Lundin Mining have emerged as the RIGI’s first benefactors thanks to their recent acquisition of Filo Corp to mine copper, gold, and silver in Argentina.

“For miners, [the] RIGI guarantees the benefits of stability for 30 years, a crucial factor in a country with a history of dramatic economic and political changes affecting foreign investment,” Federico Gay, principal lithium analyst at Benchmark, says.

“The RIGI could represent a turning point in Argentina’s lithium story,” Flavia Royon, a former Argentine mining secretary and Zelandez director, says.

“A healthy mining sector depends on long-term thinking, and this bill is built around that idea. It creates a major win-win scenario for all involved in our lithium industry - and secures our role as an important upstream player in the global energy transition.”

The IRA currently prevents the United States from fully taking advantage of the RIGI - and Argentina’s upward trajectory. Designed to speed up the American energy transition and increase investment in battery raw materials mining, the 2022 bill includes EV tax credits for consumers as long as battery components have been sourced in the US or free trade partner countries.

For the $3750 critical mineral tax credit, at least 50 percent—rising to 80 percent in 2027—of the critical minerals contained in EV batteries must be extracted or processed in the US or a nation with a free trade agreement with the US. Unlike fellow lithium producers Australia and Chile, Argentina has no free-trade agreement with the US.

Ultimately, the IRA’s rules on Foreign Entities of Concern (FEOC) are the biggest hurdle. The stipulations mandate that US EV batteries with critical minerals extracted, processed, or recycled in the FEOC nations of China, Russia, North Korea, or Iran—or by a company with more than 25 percent FEOC ownership in a third country—will not be eligible for the credits at all.

China has a significant role in Argentina’s lithium industry, with Ganfeng, Tianqi Lithium, and CATL large, long-term players. Between 2020 and 2023, Chinese lithium companies poured $3.2 billion into Argentinian projects. Though market uncertainty has seen many Western miners scale back operations this year, China’s financial stability in Argentina’s lithium brine fields is noteworthy.

Chinese investments in the Argentine brine fields have been paying off. Last year, 43 percent of the lithium produced went to China, 25 percent to Japan and 11 percent to South Korea. Just 11 percent headed to the United States.

Though some have suggested Argentina should diversify lithium mine ownership away from FEOC to take advantage of the IRA, in fact it is the US that shoulders the responsibility to move first and bring Argentina under its critical minerals umbrella.

There have been some positive signs the US is doing just that. In July 2023, the US-based International Finance Corporation—the private investment arm of the World Bank—provided a loan of up to $180 million for Allkem’s Sal de Vida lithium project in Catamarca province. Arcadium now runs it.

Argentina was recently named a new member of the US-led Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), a forum promoting “friend-shoring” of strategically important mineral resources like lithium. Last month, the US approached Indonesia, which has deep reserves of energy transition-crucial minerals like nickel, about joining the MSP.

Argentina’s MSP membership draws it closer to the US in a geostrategic sense, lining up with the South American nation’s far more US-friendly foreign policy approach under Milei.

Though a full free trade agreement between the United States and Argentina is considered unlikely, a more limited ‘Japan-style’ trade agreement has been suggested. Focused on certain agricultural and industrial products, the Trump administration-negotiated agreement with Japan demonstrates the potential to carve out a need-specific trade channel. Though negotiations were described as “close” more than a year ago, the two nations have yet to reach an agreement.

Production is ramping up in Salar Centenario, while more plants in Argentina’s Northwest will soon feature in headlines announcing their commissioning. Argentina’s lithium clock is starting to tick louder and louder for the United States

“Argentina is telling the world ‘when it comes to lithium mining, we are ready to do business,’ Royon says. “I’m confident our energy transition partners across the world will respond the right way.”

Ben Stanley

September 16, 2024

Feature

When it comes to America’s fast-growing lithium brine industry, there are few places more important than Union County, Arkansas.

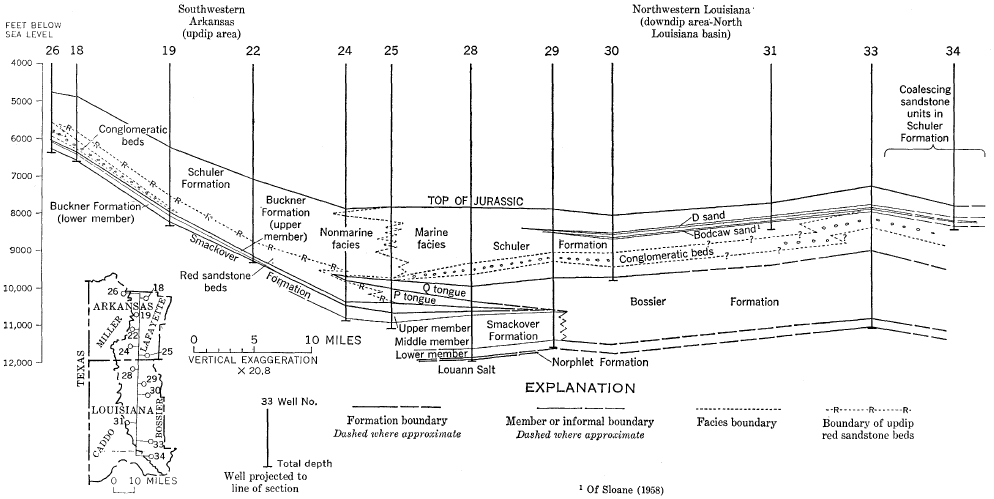

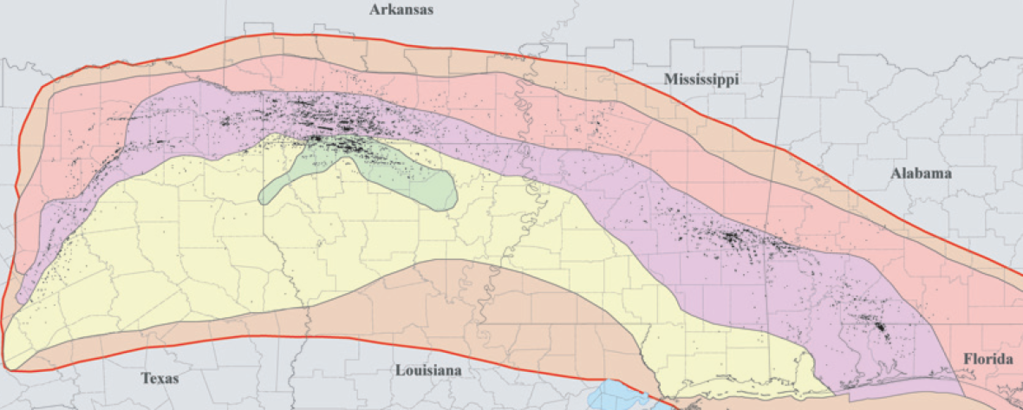

Located on the Louisiana border, Arkansas’s largest county sits above the Smackover Formation, a three-state geological area that has provided the United States with oil and bromine since the 1920s.

Though relatively high lithium concentrations have long been detected in South Arkansas oilfield brine, a range of factors—from different impurity profiles and climate to limited space and public support for large evaporation ponds—have meant extracting it hasn’t been possible. Now it looks likely that Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) technology will soon change the game.

Oil industry heavyweight ExxonMobil, lithium giant Albemarle, and a partnership between Standard Lithium and Equinor are committed to lithium production in the region. All three have Union County-located leases, with Standard Lithium’s DLE pilot column currently in advanced testing.

While a DLE-powered lithium boom will be welcomed in the county seat of El Dorado and the state capital of Little Rock, recent decades have seen Union County’s place in the American resource landscape best defined by how well it has managed and conserved its groundwater.

Faced with a fast-diminishing water table in the late 1990s, Union County residents instituted a nation-leading groundwater management scheme that has almost completely recharged the Sparta Aquifer—located above the lithium-rich Smackover—while enabling bromine brine extraction to continue. The South Arkansas plan came decades before the public alarm and widespread state legislature reaction to America’s current groundwater depletion crisis.

Given that one of the key questions around DLE’s commercial feasibility is how much fresh water the technology will use, it almost seems fated that this early American road test of selecting separating lithium ions from lithium-rich brine would take place in South Arkansas.

“If we cannot do a good job of recycling that water and reducing our water footprint, we’re going to get crushed,” John Burba, executive chairman of International Battery Metals, told Reuters last September, talking about DLE’s fresh water usage. “DLE is a very water-intensive process.”

Groundwater is the world’s most extracted raw material, providing almost half of global drinking water. Around 70 percent of all groundwater extracted is used by agriculture, which plays a significant role in ensuring we stay fed.

States with large populations and extensive farmlands tend to have the most significant groundwater withdrawals in America. In 2015, just five states—California, Texas, Idaho, Nebraska, and Arkansas—accounted for 54 percent of national groundwater use, primarily for irrigation.

Across the board, excessive water pumping, increasing droughts, and government incentives to increase food production have all affected aquifer recovery time. The overall result has been troubling.

Last August, the New York Times published an extensive investigation on groundwater usage in the United States. The findings were damning. After analyzing water levels at more than 80,000 monitoring wells across the U.S., the Times found that nearly half have “declined significantly [since the early 1980s] as more water has been pumped out than nature can replenish.”

Since 2014, 40 percent of sites have hit all-time lows. Top agricultural producers, like the ones listed above, are amongst the worst-performing states.

“From an objective standpoint, this is a crisis,” Warigia Bowman, a law professor and water expert at the University of Tulsa, told the Times, “There will be parts of the U.S. that run out of drinking water.”

Nearly three decades ago, Union County saw this coming — and acted. In 1996, the Arkansas state government designated the Sparta Aquifer beneath South Arkansas as a ‘Critical Groundwater Area.’

The following year, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) found the aquifer was dropping by as much as two meters a year. It recommended that future groundwater withdrawals in Union County be cut by nearly three-quarters to maintain water levels. Industrial requirements for freshwater played a big role in the aquifer’s diminishment.

“If we didn’t do something in five years or less, we were going to lose our water source,” Sherrel Johnson, the projects manager for the Union County water conservation board, told the Scientific American earlier this year.

Union County residents petitioned Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee—father of current Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders—to appoint a Water Conservation Board endowed with the authority to tax.

After kicking off a county-wide education program about the state of their aquifer, the board enacted a ‘conservation’ pumping fee for industrial users. Next, it instituted a voter-endorsed temporary tax for a $65 million treatment plant, drawing surface water from the nearby Ouachita River. The treated river water was explicitly for industrial users, placing far less pressure on the previously vulnerable water table.

The result of the water board’s moves has been a smashing success. This year, the overall level of the Sparta Aquifer was 36 meters higher than in 2004. All eight of USGS’s monitoring wells across the county have shown continual increases over the last two decades. In April, one well showed water levels were now higher than the top of the aquifer itself.

“You have to have trusted leadership, [good] science, and tenacity [to make the necessary changes],” Johnson said.

Union County isn’t alone in its efforts around the U.S. Aquifer Storage and Recovery schemes are active in cities across the Western United States, with Austin, San Antonio, and California’s Central Valley leading the way.

Since 2008, the $450 million San Juan-Chama Project has led to the recovery of the aquifer beneath Albuquerque, New Mexico, and lifted fresh water supplies for farmers along the Rio Grande River.

At best, the Federal approach to America’s groundwater crisis could be called stunted. At worst? Deeply disappointing. Over recent years, Senator Martin Henrich, a New Mexico Democrat, has championed the cause of groundwater management and conservation in Washington, D.C., introducing a raft of bills.

His Voluntary Groundwater Conservation Act—co-sponsored by Senator Jerry Moran, a Republican from Kansas—would give American farmers more flexibility and incentives to protect groundwater sources. Heinirch's Water Data Act has the potential to transform water management by establishing a national requirement for collecting information about groundwater.

Currently, many states require little, if any, monitoring or reporting on their aquifers. For their deeply researched investigation into the state of American groundwater, the Times used figures from 60 different databases, each with its categories of interest and levels of completeness.

Neither of Heinrich’s bills have been voted on.

Further down the American governance chain, there’s more encouraging movement. Last October, the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), a bipartisan group representing state governments across the U.S., highlighted many encouraging groundwater-focused laws passed in red and blue states over recent years.

Since 2019, more than 100 state bills focusing on groundwater conservation and management have been made law. In the last two years, Virginia, Idaho, Kansas, Utah, and Nevada all passed laws that focused on conserving aquifers and basins.

Passed in 2020, the Utah Water Banking Act has enabled water rights holders with extra water to lease it to those with less. The state is planning on expanding the program. Along with revising current groundwater management provisions, Nevada introduced a law last year that requires the state engineer to “affirm or modify the perennial yield of basins in designated critical management areas.” Both Utah and Nevada have a crucial role in America’s lithium future.

Extraction policies have changed, too. A number of states require further permitting, higher fees for extraction in conservation areas, and plans for water auditing and leak detection and repair. California, Oklahoma, Nevada, Texas, and Virginia are among the states leading the way.

Other measures are possible. Writing for Forbes last October, John Sabo, a Tulane professor focusing on water resources at the school’s ByWater Institute, identified three ways to improve the groundwater situation in the Mississippi River Valley.

These were determining how to better capture excess water from downpours and floods and store it underground, establishing an interstate compact to help coordinate conjunctive groundwater and surface water management, and reevaluating how water is used in agriculture, including which crops are grown where.

There are international examples to replicate, too. Several recharge pilot schemes in central Spain have utilized rooftop runoff and treated wastewater to refill aquifers. After new fees were introduced for private well pumping in Bangkok in the early 2000s, groundwater losses were reversed, and land subsidence issues slowed.

Since 84 percent of all groundwater withdrawals are freshwater, the extraction of saline aquifers makes up less than a sixth of all water drawn from beneath the surface in the United States.

Ninety-seven percent of saline groundwater is used for thermoelectric energy, two percent for industrial needs, and just one percent for mining—a figure that will quickly increase as drilling for DLE-enabled brines becomes more feasible and environmentally friendly.

The entire lithium industry has been working on strategies to increase freshwater recycling, aiming to ensure lithium extraction from brine remains feasible from a resource management standpoint. Freshwater requirements for DLE will vary from design to design.

Reuters reported that some types of DLE technology require 180 metric tons of water to produce one metric ton of lithium, which does little to support DLE’s transformational claims. In the ion-exchange DLE process, for instance, fresh water is required to rinse the sorbent from the lithium. Careful recycling of this freshwater input will in many instances also be required.

Last year, French researchers published a paper on the environmental impact of DLE from brines. After analyzing 57 reports on water-dependent DLE technology, they found a quarter showed freshwater usage at rates up to ten times higher than evaporation ponds used in South America. Another quarter of the DLE tech they studied had no freshwater usage data at all.

Encouragingly, Albemarle uses membrane-based DLE tech at its Union County pilot plant, a technique that some recognize as requiring less water for operations. ExxonMobil is still researching which DLE technology to use, while Standard Lithium has spoken with confidence about the efficency of their Koch Industries-engineered system.

Due to the presence of the Ouachita River and the county’s treatment plant, fresh water is relatively abundant on the Arkansas side of the Smackover. Industry has continued successfully in Union County, utilizing water from the plant. Since 2007, all of America’s bromine supply has been sourced from South Arkansas brine.

Johnson, of the Union County Water Conservation Board, says their publicly funded water plant has “proven a boon for luring new development,” which includes lithium brinefield operators.

Another challenge lithium miners face in Union County is that the Sparta Aquifer sits directly above the Smackover itself. Careful engineering and properly designed drilling and pumping technology is an absolute must.

Whatever happens, you can be sure the Union County Water Conservation Board will be watching the levels. In one of DLE tech's early road tests n South Arkansas brine, a suitable water watchdog is firmly in place.

Ben Stanley

July 17, 2024

Feature

Zelandez is thrilled to announce that Flavia Royon, Argentina’s former Secretary of Energy and Mining, will join the company’s board as a director.

The appointment ensures that the world’s leading lithium brinefield technology provider will have a crucial Argentinian perspective on operations as the South American nation further strengthens its position as one of the world’s largest lithium suppliers.

“Argentina is set to play an essential strategic role in the world’s energy transition moving forward, and Zelandez will be a crucial partner in making that happen,” Royon says. “Having an Argentinian at the top table with Zelandez is a big win for both parties.”

A trained industrial engineer, Royon served as the Secretary of Mining and Energy for Salta province before serving as Argentina’s Secretary of Energy between 2022 and 2023. Royon was appointed Secretary of Mining by President Javier Milei in December 2023, a role she left this February. She will officially start as a Zelandez board member later this month.

Gene Morgan, Zelandez’s chief executive, says Royon’s extensive experience and understanding of the Argentine lithium mining sector will give the company an invaluable perspective.

“From Salta to the halls of power in Buenos Aires, Flavia knows what it takes to ensure lithium brine mining benefits all stakeholders,” Morgan says. “Along with her commitment to community engagement, her insight will be a huge asset for Zelandez.”

Royon described Zelandez’s reputation as a pragmatic, honest broker in the South American lithium brine industry as a key reason she agreed to join its board.

“Whether you work as a brinefield engineer or as a policymaker on the provincial or national level, Zelandez has built up the reputation as a professional, dependable partner on South America’s brinefields,” she says.

“As a board member, I am dedicated to strengthening that reputation and showing my fellow Argentinians why our nation can benefit from the lithium brine mining process.”

Forming part of South America's ‘lithium triangle’, Argentina is currently the world’s fourth largest lithium producer, providing around 34,000 tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) annually. By 2027, it is estimated to grow significantly, surpassing Chile as the world’s second-largest producer.

Last month, Zelandez partnered with the Argentine province of Catamarca in an agreement to provide modular prefabricated plants for the nation’s top lithium-producing state. The central element of the partnership is the supply and utilization of ErLi, Zelandez’s prefabricated lithium production facilities.

Media Team

July 9, 2024

Press

Zelandez has partnered with the Argentinian province of Catamarca in an agreement to provide modular prefabricated plants for the South American nation’s top lithium-producing province.

The partnership links the world’s leading lithium brine technology provider with Catamarca’s mining and energy company.

Prefabricated lithium carbonate production plants form the partnership’s central element, which Zelandez will build in the United States.

Gene Morgan, Zelandez’s chief executive, says a formal partnership with CAMYEN felt like a natural progression for the two organizations and a “major win for stakeholders in the Argentinian lithium industry and its supply line to the United States.”

"Zelandez has long been serving clients in the state of Catamarca, and we have enjoyed the pragmatic way that the region seeks to assist local lithium production,” Morgan says. “This partnership aims to help all our clients in the region."

"We welcome this engagement with Zelandez as a way to continue to add value to the province's lithium resources, create jobs, and generate export income," Susana Prelate Molina, the president of CAMYEN, says.

The agreement will also see Zelandez and CAMYEN team up to facilitate future project finance partnerships from the United States, Europe, and Japan. Under Argentinian law, provinces retain mineral resource rights.

By 2027, Argentina is estimated to grow lithium production significantly, surpassing Chile as the world’s second-largest lithium producer. Today, around 20,000 tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) is produced annually from Catamarca’s brinefields, representing more than half of Argentina’s overall production. Most the nation’s lithium brine exploration projects also occur in the province.

Catamarca is located at the heart of South America’s "Lithium Triangle," which contains more than 60% of the world’s total lithium reserves in brine formations. South American brine-sourced lithium is considered the lowest-cost source of the battery-critical element.

About Zelandez

Zelandez is the leading services provider to the lithium brine industry. The company provides a comprehensive suite of advanced resource exploration and production tools. Zelandez also offers complete wrap-around integrated services for lithium mining companies designed to accelerate the path to lithium production. Zelandez works with leading lithium mining companies in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, the United States, and Canada.

About CAMYEN

CAMYEN is the mining and energy company of Catamarca Argentina, and its main objective is the development of Catamarca's mining and energy, through the sustainable use of natural resources and the preservation of the environment while society continues developing. CAMYEN holds mining rights by way of business contracts and company collaborations in the lithium market in the region.

Learn more about Zelandez here.

Media team

June 29, 2024

Press

Austin, Texas, March 5, 2024 — Zelandez, the leading provider of technology to the

lithium brine industry, today announced the availability of its new Borehole Formation

Tester (BFT) to lithium developers worldwide.

The BFT is the world’s slimmest pump-through formation tester designed to specifically address lithium miners’ needs by measuring aquifer pressure, analyzing fluids downhole in real-time, and obtaining representative brine samples. It significantly reduces the costs of lithium brine development when compared to the less accurate incumbent ‘packer testing method’.

Lithium developers will no longer depend on large expensive rig-deployed sampling, which has high supply costs, to retrieve brine samples from below ground. The BFT reduces the time needed to sample quality lithium brine. Contaminated brine samples will become a thing of the past.

The BFT provides detailed pressure and productivity data and allows clients' hydrogeology teams to optimize brine and lithium production. It speeds up the development period required to bring lithium to market at a lower cost.

Currently, no product or service offers lithium operations the level of pressure measurement, fluid characterization, and reservoir testing that the BFT does.

“The world needs more lithium. The old way of sampling lithium was just too slow and too cumbersome. It was making it hard to find new lithium brine resources and to bring more lithium to market. The Borehole Formation Tester changes that - it changes the game for lithium developers. The BFT is another example of Zelandez innovating specifically for the needs of the lithium market,” said Gene Morgan, CEO of Zelandez.

“The BFT was built to address the specific challenges of aquifer testing and fluid sampling in lithium brine exploration and production. Instead of it taking weeks, it delivers results within hours or days.”

The BFT enables the lithium mining industry to conduct rigless pressure and permeability testing and fluid sampling in slim boreholes down to 122mm (PQ). The BFT provides testing and sampling in low permeability, laminated, fractured, unconsolidated, and heterogeneous formations. It enhances lithium miners’ decision- making by delivering real-time access to actionable aquifer data. Through enhanced definition of the complex sub-surfaces poor well deliverability is mitigated.

It also enables miners to understand better and meet their reinjection requirements.

“While Formation Testers are commonplace in the Oil and Gas industry, their size and cost have made them impractical for use in the brinefield. The BFT has miniaturized this technology for lithium miners” adds Morgan.

Zelandez’s BFT serves the testing and sampling needs of the lithium brine, groundwater, hard rock, coal seam gas, natural hydrogen, and helium sectors.

Zelandez is the leader in brinefield services and provides a comprehensive suite of technology for lithium brine explorers and producers, including full wrap-around integrated project management, modular lithium production plants, sensors, and expert geoscience and engineering know-how. Zelandez works with the majority of lithium mining companies in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile and North America.

For More Information

Matt Adams

BFT Director of Sales

Tel: +61 467 726 027

E-Mail: [email protected]

Matt Adams

March 19, 2024

Uncategorized

Choose Zelandez for your lithium brine project